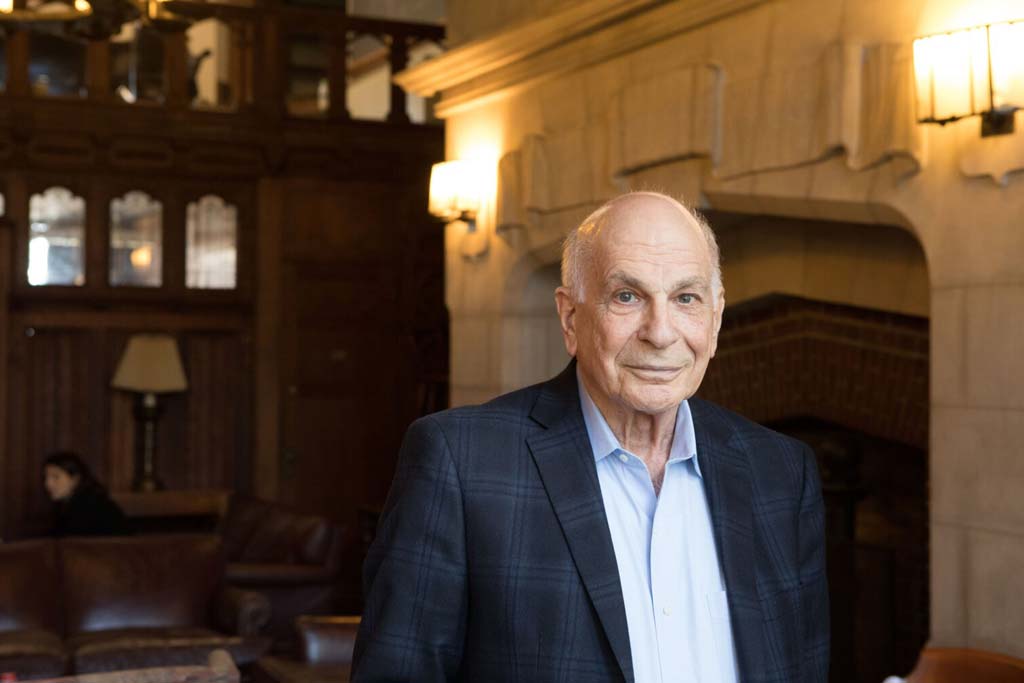

Human decisions driven by instinct shocked me as I scrolled through the BBC’s ‘Notable Deaths 2024’ article last December. Daniel Kahneman was among the list of influential people who had passed away.

My heart sank. How had I missed this news? The Nobel Prize-winning psychologist whose work fundamentally changed our understanding of how people make choices had died, and I’d failed to acknowledge it properly.

The oversight bothered me for weeks. After all, Kahneman’s masterpiece “Thinking, Fast and Slow” sits on my bookshelf, filled with my highlights and notes from years ago. His insights into the human mind profoundly influenced my approach to research, coaching, and even personal decision-making. Like figures like Nelson Mandela and Hans Rosling, Kahneman challenged established thinking and left an indelible mark on our collective understanding.

What made Kahneman’s contribution so vital was his challenge to a cornerstone of economic theory—that humans are rational beings who consistently act in their self-interest. Instead, he demonstrated that our choices often stem from automatic, instinctual processes that frequently lead us astray. His work laid bare the machinery behind our flawed thinking, showing how quick judgements can override careful analysis.

The BBC’s short tribute described how Kahneman “took issue with one of the central ideas underlying economics” and “suggested that, on the contrary, people often act irrationally, based on instinct.” This simple summary captures the essence of his revolutionary work—work that earned him the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics despite being a psychologist by training.

In the months since his passing, I’ve revisited my electronic notes on “Thinking, Fast and Slow” and reflected on its lessons. The insights within those notes reveal the fascinating mechanisms behind human judgement and decision-making, explaining why we consistently make predictable errors when faced with uncertainty. Through careful experiments and thoughtful analysis, Kahneman mapped the invisible forces that shape our choices, from our aversion to losses to our tendency to substitute simple questions for difficult ones.

The following section examines Kahneman’s most important ideas, how they continue to influence fields from medicine to public policy, and why understanding the instinctual drivers of human decisions matters now more than ever.

Discovering the Two Systems Behind Human Decisions Driven by Instinct

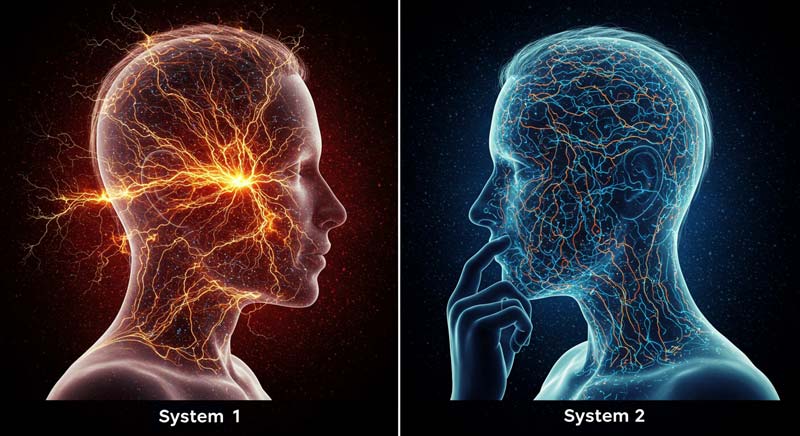

The genius of Kahneman’s work lies in his elegant framework for explaining how our minds function. He identifies two distinct modes of thinking that work together to shape human decisions driven by instinct and reason. These two systems—which he simply calls System 1 and System 2, operate in fundamentally different ways yet must collaborate constantly throughout our daily lives.

System 1: The Automatic Pilot

System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with no sense of voluntary control. It’s the source of our gut reactions, immediate impressions, and instinctual responses. When you flinch at a loud noise, recognise a friend’s face, or feel unease in a dangerous situation, System 1 is at work.

This mental mechanism evolved to help our ancestors survive in environments where quick reactions determined life or death. Even now, System 1 runs continuously in the background, monitoring our surroundings and generating interpretations of events with remarkable speed and minimal effort.

System 1 excels at pattern recognition and creates a coherent story from limited information. As Kahneman notes, “System 1 is designed to jump to conclusions from little evidence.” This ability serves us well in many situations but can lead to serious errors when the available evidence is unreliable or incomplete.

What’s truly fascinating about System 1 is its influence on human decisions driven by instinct without our awareness. We often believe we’re making considered choices when, in fact, our automatic pilot has already determined our response. The operation of System 1 explains why first impressions are so powerful and why certain biases persist even when we try to overcome them.

System 2: The Conscious Controller

System 2 represents the conscious, reasoning self that makes deliberate choices. It handles tasks requiring concentration, calculation, or self-control. When you multiply 17 × 24, follow a complex argument, or check your behaviour in a socially delicate situation, you’re engaging System 2.

Unlike the effortless operation of System 1, System 2 demands attention and energy. It’s lazy by nature, preferring to conserve mental resources whenever possible. This inherent laziness explains why we often default to mental shortcuts rather than engaging in careful analysis. System 2 simply doesn’t want to work unless it absolutely must.

“Although System 2 believes itself to be where the action is,” Kahneman writes, “the automatic System 1 is the hero of the book.” This observation captures a crucial insight: while we identify with our conscious, deliberative thinking, much of our mental life unfolds automatically and unconsciously.

When Systems Collide

The interaction between these two systems creates a fascinating dynamic. System 1 continuously generates suggestions for System 2: impressions, intuitions, intentions, and feelings. If endorsed by System 2, these suggestions become beliefs, impulses turn into voluntary actions, and intuitive judgements shape our decisions.

When all goes smoothly, which is most of the time, System 2 adopts System 1’s suggestions with minimal modification. However, when System 1 encounters difficulty, it calls on System 2 to provide more detailed processing to solve the current problem.

This partnership works beautifully in many situations. System 1’s intuitions are often accurate, especially in familiar environments where we’ve had ample opportunity to learn relevant patterns. Expert intuition, for instance, represents the triumph of System 1 learning through extensive experience.

However, System 1 also has systematic flaws. It cannot be turned off, and its biases are difficult to prevent. It’s prone to substituting easier questions for difficult ones, overweighting emotional considerations, and generating a coherent but potentially flawed narrative from the available evidence.

System 2’s job is to monitor and control thoughts and actions suggested by System 1. Yet, this supervision is often lacking. As Kahneman notes, “System 2 is sometimes busy and often lazy.” When System 2 is occupied or tired, System 1’s influence on our behaviour increases dramatically.

These two systems provide a powerful lens for examining our own behaviour. Many of our errors in judgement occur not because we’re stupid but because we’re relying on System 1 in situations where more careful analysis is required. The consistent patterns behind these errors reveal the underlying mechanisms that drive human decisions driven by instinct and reason.

The Surprising Biases and Heuristics That Shape Our Thinking

Our minds rely on shortcuts and simplifications that lead to predictable errors in judgement. Kahneman spent decades cataloguing these systematic biases, showing how they affect everything from everyday choices to major life decisions. What’s genuinely eye-opening is how these biases manifest even when we’re trying to think carefully and logically.

Anchoring: How Initial Information Distorts Judgement

The anchoring effect represents one of the most powerful influences on our thinking. When making estimates or judgements, we give disproportionate weight to the first information we encounter—the “anchor.” Even when we know the anchor is completely arbitrary, it still affects our final judgement.

In one famous experiment, Kahneman and Tversky asked participants if the percentage of African nations in the United Nations was higher or lower than a random number (10% or 65%) generated by spinning a wheel of fortune. After this initial question, they asked participants to estimate the actual percentage. Those who saw the higher anchor gave much higher estimates than those who saw the lower anchor.

This effect appears in countless situations. Initial asking prices influence house prices, and the first offer shapes salary negotiations. Even judges’ sentencing decisions can be affected by arbitrary numbers mentioned earlier in proceedings.

What’s particularly troubling about anchoring is that expertise doesn’t provide immunity. Kahneman found that the listed prices heavily influenced real estate agents’ property valuations despite their professional knowledge of the market. The anchoring effect shows how our judgements can be manipulated by information that should be irrelevant to our decisions.

Availability: Why What Comes Easily to Mind Seems Most Likely

The availability heuristic causes us to judge the likelihood of events based on how easily examples come to mind. If instances of an event are readily available in memory, we assume the event must be common.

This mental shortcut explains why people often overestimate risks that receive media attention. Dramatic events like terrorist attacks or plane crashes are vividly reported and easily remembered, making them seem more common than they actually are. Meanwhile, genuine risks like heart disease, which kills millions but generates fewer headlines, seem less threatening.

Kahneman notes that the availability heuristic leads to a predictable bias: “The world in our heads is not a precise replica of reality; our expectations about the frequency of events are distorted by the prevalence and emotional intensity of the messages to which we are exposed.”

This bias affects personal decisions as well. A doctor who has recently seen complications from a particular treatment may overestimate its risks. An investor who recalls friends losing money in the stock market may avoid investing altogether. In each case, vivid or recent examples distort judgement about actual probabilities.

Substitution: How We Answer Easier Questions Instead

One of Kahneman’s most profound insights is that when faced with difficult questions, we often answer easier ones instead, usually without noticing the substitution. He describes this as “the essence of intuitive heuristics.”

Asked, “How happy are you with your life these days?” people might answer the easier question: “What is my mood right now?” Rather than evaluating general life satisfaction (a complex assessment), they substitute their current emotional state (readily available information).

Similarly, when asked whether a political candidate would be a good president or prime minister, many voters substitute the easier question: “Does this candidate look like a leader?” Instead of assessing policy positions or executive experience, they rely on appearance and charisma—factors that may have little relevance to leadership ability.

This substitution happens automatically and unconsciously. We genuinely believe we’re answering the original question, unaware that our minds have quietly replaced it with something simpler. This explains why smart people can make poor judgements—they often solve the wrong problem.

Overconfidence and the Illusion of Understanding

Perhaps the most pervasive bias Kahneman identifies is overconfidence—our tendency to believe we know more than we do and can predict more than is possible. This manifests in several ways:

The illusion of validity appears when experts maintain strong confidence in their judgements despite evidence that their predictions are no better than chance. Financial advisers, political pundits, and sports commentators all demonstrate this illusion, continuing to make confident predictions despite poor track records.

The planning fallacy leads us to consistently underestimate how long projects will take and how much they will cost. From home renovations to major infrastructure projects, optimistic forecasts consistently fail to account for inevitable complications and delays.

Hindsight bias creates the illusion that we understood events all along. After outcomes are known, the path to those outcomes seems clear and predictable—though it rarely was in advance. This feeds overconfidence because we believe we’ll be able to predict future events just as “easily” as we explain past ones.

These biases persist because of what Kahneman calls WYSIATI—”What You See Is All There Is.” Our minds construct the most coherent story possible from available information, ignoring gaps in our knowledge. We then place excessive confidence in these incomplete stories, failing to account for what we don’t know.

The Law of Small Numbers: Why We See Patterns in Random Data

Humans are pattern-seeking creatures, quick to detect meaningful signals even in random noise. This tendency leads us to what Kahneman calls “the law of small numbers“—the mistaken belief that small samples closely resemble the populations from which they are drawn.

When a hospital records five baby boys born in succession, people wonder about the cause. When an investment strategy succeeds three times in a row, it is a winning approach. When a basketball player makes several consecutive shots, commentators declare them to have a “hot hand.”

People underestimate how much randomness produces streaks and patterns by chance alone in each case. Small samples are much more likely to deviate from the average than large ones. Yet, we treat these deviations as meaningful and seek explanations.

This bias explains why anecdotal evidence is so persuasive despite its statistical insignificance. A few vivid stories often outweigh large-scale statistical evidence in our judgements, leading to poor decisions based on inadequate samples.

The law of small numbers reveals a fundamental limitation in human intuition about randomness. We struggle to accept that many events in life result from chance rather than discernible causes. This limitation affects everyone, from gamblers to scientific researchers.

Prospect Theory: How We Evaluate Risk and Value Differently

Before Kahneman and his research partner Amos Tversky introduced Prospect Theory in 1979, economists relied on Expected Utility Theory to explain how people make risk decisions.

The conventional model assumed people were rational actors who consistently maximised their expected utility when faced with uncertain outcomes. Prospect Theory revealed this assumption was fundamentally flawed, offering instead a psychologically realistic account of how people actually evaluate options.

Loss Aversion: Why Losses Hurt More Than Gains Feel Good

At the heart of Prospect Theory lies a powerful asymmetry in how we respond to gains and losses. Kahneman’s research showed that losses loom larger than corresponding gains, a phenomenon he called loss aversion. The pain of losing £100 is more intense than the pleasure of gaining the same amount, typically by a factor of about 1.5 to 2.5.

This asymmetry shapes countless decisions. Homeowners refuse to sell properties for less than they paid, even when holding on costs them more. Investors hold onto losing stocks too long, hoping to break even. Companies stick with failing strategies rather than admit defeat and try something new.

Loss aversion also explains why identical outcomes can be perceived differently depending on how they’re framed. For example, when a doctor describes surgery as having a “90% survival rate,” it sounds more appealing than the identical information framed as a “10% mortality rate.” The first frame emphasises gains (lives saved), while the second highlights losses (deaths).

This principle extends beyond financial decisions. In relationships, negative interactions typically have stronger effects than positive ones. Relationship expert John Gottman found that stable marriages require at least five positive interactions to offset each negative one, a ratio that reflects our greater sensitivity to losses than gains.

Reference Points and Relativity

Another key insight from Prospect Theory is that we evaluate outcomes relative to a reference point, not in absolute terms. A £20,000 salary increase feels very different to someone earning £30,000 versus someone earning £300,000. Similarly, a 3°C temperature drop is pleasant in summer but unpleasant in winter.

These reference points shift constantly. A person who receives a raise might temporarily feel wealthier but soon adapts to the new income level, which becomes their new baseline. This “hedonic adaptation” explains why material improvements often provide only temporary happiness boosts.

Reference points also create interesting inconsistencies in our preferences. A person might drive across town to save £7 on a £25 item but not to save the same £7 on a £495 purchase—though the absolute saving is identical. Our reference point (the item’s base price) determines whether the saving seems significant.

Understanding reference points provides powerful insights into marketing strategies and public policy. Retailers highlight “sale” prices compared to “regular” prices to establish advantageous reference points. Similarly, governments might frame tax changes as “credits” rather than “reduced surcharges” to enhance their appeal.

The Fourfold Pattern of Risk Preferences

Prospect Theory reveals a consistent pattern in how people respond to different combinations of probability and outcome valence (positive or negative). This “fourfold pattern” explains apparently contradictory risk attitudes:

People are risk-averse when it comes to high-probability gains. Most would prefer a certain £900 over a 90% chance of £1,000. The potential disappointment of missing out on a nearly certain gain leads to cautious choices.

People become risk-seeking for low-probability gains. Despite the identical expected value, many prefer a 5% chance of £1,000 over a certain £50. This explains the widespread appeal of lotteries.

People turn to risk-seeking for high probability losses. Most prefer a 90% chance of losing £1,000 over a certain loss of £900. When facing a likely loss, people often take desperate risks to avoid it entirely.

For low-probability losses, people become intensely risk-averse. Many pay insurance premiums far exceeding the expected value of potential losses. The possibility of a catastrophic outcome drives precautionary behaviour, even when quite unlikely.

This pattern explains why the same person might buy insurance (risk aversion for low-probability losses) and lottery tickets (risk seeking for low-probability gains)—behaviours that seem contradictory under traditional economic theories.

The Endowment Effect and Status Quo Bias

Loss aversion creates additional effects that influence everyday decisions. The endowment effect causes people to value items more highly once they own them. In classic experiments, people required significantly more money to give up a coffee mug they’d been given than they were willing to pay to acquire the same mug.

This affects negotiations and market transactions. Sellers value their goods more highly than buyers, creating a gap that can prevent mutually beneficial exchanges. House sellers often overvalue their properties based on personal attachments and improvements that buyers don’t value equally.

Related to this is the status quo bias—our tendency to prefer the current state of affairs. Changing from the status quo creates potential losses that loom larger than potential gains, leading to inertia. This explains why default options on forms (like organ donation or retirement savings) so powerfully influence outcomes.

These effects challenge traditional economic accounts of human behaviour. Rather than coolly calculating expected values, people make choices influenced by reference points, loss sensitivity, and status quo preferences—psychological factors absent from classical economic models.

Practical Applications of Prospect Theory

Kahneman’s insights into risk evaluation have transformed fields from marketing to medicine and finance to public policy. Understanding these patterns helps explain otherwise puzzling behaviours and suggests ways to improve decision-making.

In medicine, doctors can present treatment options in ways that help patients make choices aligned with their true preferences rather than being swayed by framing effects. For example, describing outcomes in both survival and mortality terms provides a more balanced perspective than either frame alone.

In finance, awareness of loss aversion helps investors avoid common mistakes like losing investments too long or taking insufficient risks in long-term portfolios. Some investment firms now employ “commitment devices” that prevent clients from making impulsive decisions during market downturns.

In public policy, understanding reference points and loss aversion improves program design. For instance, tax refunds feel like gains and are often saved, while additional withholding feels like losses and generates resistance—though the economic impact is identical.

For individuals, recognising these patterns provides a valuable defence against poor decisions. By consciously reframing choices, considering multiple reference points, and recognising when loss aversion might lead us astray, we can make choices more aligned with our true interests.

Human Decisions Driven by Instinct in Everyday Life

The brilliance of Kahneman’s work lies in its wide-ranging applications to ordinary situations. The psychological mechanisms behind human decisions are driven by instinct and affect everything from how we shop to how we save, from medical choices to personal relationships. Examining these everyday contexts can help us better understand and potentially improve our decision-making.

Financial Choices: Why We Make Poor Investment Decisions

Our financial lives offer a perfect laboratory for observing the quirks of human judgement. Consider these common behaviours that contradict traditional economic wisdom:

- Investors frequently check their portfolios during market volatility, a habit that amplifies emotional responses to short-term fluctuations and often leads to panic selling at market bottoms. Kahneman recommends checking investments less frequently to avoid this emotional rollercoaster.

- Many people maintain separate mental accounts for different financial goals, treating money differently based on its intended purpose. They might simultaneously save money in a low-interest account while carrying high-interest credit card debt, A mathematically irrational approach that makes emotional sense due to mental accounting.

- Risk attitudes shift dramatically depending on context. The same person who buys insurance to avoid small losses might take substantial risks in hopes of avoiding larger losses. This explains why financially distressed companies often make increasingly risky business decisions; when facing likely failure, the possibility of avoiding loss altogether becomes irrationally attractive.

- Perhaps most significantly, financial decisions reveal our struggle with intertemporal choice, decisions involving different points in time. We consistently favour immediate rewards over future benefits, even when the future benefits are substantially larger. This present bias helps explain inadequate retirement savings, difficulty maintaining exercise routines, and challenges in adhering to healthy diets.

- Human decisions driven by instinct appear clearly in studies of investor behaviour. Most individual investors underperform market indices not because they lack information but because their psychological biases lead to poor timing decisions, buying high out of excitement and selling low out of fear. The pain of losses drives many investors to make their worst decisions precisely when clear thinking is most needed.

When Experts Fail: The Limits of Professional Intuition

We often trust experts with important decisions, assuming their experience guarantees good judgement. However, Kahneman’s research reveals that expert intuition is reliable only under specific conditions:

- First, the environment must provide valid, consistent cues that the expert can learn through extensive practice. Chess masters develop reliable intuition because the rules never change, and feedback is immediate and clear.

- Second, experts must have adequate opportunity to learn these regularities through prolonged practice and feedback. Without sufficient practice in a stable environment, apparent expertise may reflect confidence rather than skill.

Many professional environments fail these conditions. Financial markets, for example, provide inconsistent patterns and delayed noisy feedback. This explains why stock pickers and economic forecasters perform so poorly despite their credentials and confidence.

Even experienced professionals like doctors, judges, and hiring managers fall prey to biases like the halo effect (allowing one positive trait to influence overall evaluation) and confirmation bias (seeking evidence that supports pre-existing beliefs). In one striking study, experienced radiologists given the same X-ray on different occasions made inconsistent diagnoses up to 20% of the time.

Most troublingly, experts are typically unaware of these limitations. Kahneman warns about an “illusion of skill“, the belief in expertise despite evidence to the contrary. This illusion persists because our minds construct coherent narratives that explain past events, creating an illusion that the future is similarly predictable.

Defence Against Poor Decisions: Practical Techniques

While we cannot eliminate our cognitive biases, Kahneman suggests several strategies to mitigate their effects:

Use formulas and algorithms where possible. Even simple statistical models typically outperform expert judgement in many domains. When hiring employees, for example, a standardised scoring system based on key criteria typically yields better results than unstructured interviews.

Widen your frame of reference. Taking the “outside view” means looking at how similar situations typically unfold rather than focusing solely on the specific case. When planning a project, consider how long similar projects took rather than building a detailed yet optimistic timeline.

Conduct a “premortem” before major decisions. Imagine your plan has failed, then work backwards to identify what might have gone wrong. This technique helps counteract optimism bias by legitimising doubts and identifying potential problems before they occur.

Create decision checklists for recurring choices. Especially when tired or under pressure, checklists help ensure all relevant factors receive consideration. Surgeons who use checklists, for example, make fewer errors than those who rely solely on memory and training.

Perhaps most importantly, recognise situations where intuition is likely to mislead you. Decisions involving statistics, rare events, or long-term outcomes are particularly vulnerable to bias and benefit most from structured approaches.

Social Decisions: The Hidden Drivers of Relationships

Our social interactions also reveal the influence of automatic mental processes. The fundamental attribution error leads us to explain others’ behaviour regarding personality traits while attributing our actions to situational factors. When a colleague misses a deadline, we see irresponsibility; when we miss one, we blame our overloaded schedule.

First impressions exert an outsized influence on subsequent judgements through the halo effect. A job candidate who appears confident in the first minutes of an interview benefits from this positive initial impression throughout the entire evaluation process.

We also display consistent biases in how we judge others’ abilities. In group settings, we often confuse confidence for competence, leading the most assertive (rather than the most knowledgeable) members to exert the greatest influence.

Most poignantly, we consistently mispredict what will make us and others happy, a phenomenon Kahneman calls “focusing illusion.” We overestimate the impact of both positive and negative changes in our circumstances (promotions, relocations, even disabilities) because we focus on the change itself rather than on the many aspects of life that remain unchanged.

These social judgement biases help explain persistent issues like workplace discrimination, political polarisation, and miscommunication in relationships. By recognising these patterns, we can adopt more thoughtful approaches to social interactions and avoid common pitfalls in interpersonal judgement.

The Conflict Between Our Experiencing and Human Decisions Driven by Instinct

The most profound of Kahneman’s insights concerns a fundamental split within ourselves, a division that shapes our happiness, memories, and choices. We exist, he argues, as two distinct selves:

- An experiencing self that lives in the present moment

- A remembering self that keeps score and makes decisions.

This division explains many puzzling aspects of human decisions driven by instinct and behaviour.

The Remembering Self vs. The Experiencing Self

The experiencing self lives in the continuous present. It answers the question, “How do I feel right now?” This self registers pain, pleasure, satisfaction, and boredom as they occur, moment by moment. However, it has no voice in our future decisions because it lacks the ability to form memories.

The remembering self, by contrast, keeps track of our life story. It answers the question, “How has my life been?” This self creates and maintains the narrative of our experiences, but it follows peculiar rules in how it constructs memories. Most notably, it ignores duration, focusing instead on peak moments and endpoints.

This split creates a profound conflict. As Kahneman puts it, “What makes the experiencing self happy is not quite the same as what satisfies the remembering self.” The experiencing self prefers to minimise pain and maximise pleasure throughout an experience. The remembering self cares about the story—particularly how it ends.

In medical procedures, for example, the experiencing self wants the shortest possible duration of discomfort. The remembering self, however, would prefer a longer procedure that ends with diminishing pain rather than a shorter one that ends with intense pain. The memory of the event, not the experience itself, determines which option we choose when faced with the same situation again.

Duration Neglect and the Peak-End Rule

Through clever experiments, Kahneman discovered that our memories of past experiences follow predictable patterns. We largely ignore how long experiences last (duration neglect) and instead form memories based primarily on two key moments: the peak intensity and the endpoint (the peak-end rule).

Participants underwent two versions of an uncomfortable cold-water immersion in one famous study. In the first trial, they kept one hand in painfully cold water for 60 seconds. In the second trial, they endured the same 60 seconds followed by an additional 30 seconds during which the water was gradually warmed (still uncomfortable but less so). When asked which trial they would repeat if necessary, most chose the longer experience, objectively, the option that imposed more total pain.

This counterintuitive choice demonstrates the tyranny of the remembering self. When making decisions, we prioritise creating good memories over having good experiences. We choose based on anticipated memory rather than anticipated experience.

This principle operates in everyday life, too. A wonderful holiday with a miserable final day may be remembered as primarily negative. A mediocre film with a satisfying ending leaves a better impression than a brilliant film with a disappointing conclusion. These patterns explain why experiences designed to create positive memories, like holidays, concerts, or meals, typically include a deliberately crafted ending.

Happiness and Life Satisfaction: Two Different Stories

The distinction between experiencing and remembering selves extends to how we evaluate our lives overall. Kahneman distinguishes between experienced well-being (moment-by-moment happiness) and evaluative well-being (satisfaction with life when we reflect on it).

These two forms of well-being often diverge. Factors that improve moment-by-moment experience may have little impact on life evaluation and vice versa. Income illustrates this divergence clearly. Beyond a moderate income that meets basic needs, additional money does little to improve everyday happiness but continues to boost life satisfaction.

This helps explain why people make choices that don’t maximise their daily happiness. A high-paying job with long hours and high stress may reduce experienced well-being while enhancing life evaluation. Similarly, having children typically increases life satisfaction while decreasing average daily happiness, a trade-off the remembering self finds worthwhile.

The implications extend further into human decisions driven by instinct. When planning for the future, we typically imagine how we’ll evaluate our experiences rather than how we feel during them. This leads to choices that optimise for good stories rather than good experiences, a pattern that becomes problematic when the gap between the two grows too large.

Memory, Time, and Attention

Kahneman’s research reveals that our relationship with time is largely mediated by attention. “Nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you’re thinking about it,” he writes, describing what he calls the “focusing illusion.”

When making decisions, we focus on what will change rather than what will stay the same. Moving to California for better weather seems like it will substantially improve happiness because we focus on climate differences. In reality, the weather occupies little of our attention in daily life, so its impact on overall happiness is minimal.

Similarly, we focus on future events in isolation rather than considering them in the context of our overall lives. A desired promotion seems like it will transform our happiness because we focus on the changes it will bring, such as higher status and better pay, while overlooking the many aspects of life that will remain unchanged.

This focusing illusion explains why we consistently mispredict what will make us happy. Major life changes, both positive and negative, typically have less impact on our daily experience than we anticipate because our attention gradually shifts away from these changes as they become familiar.

The difference between attention and happiness creates a particular challenge for modern life. In a world of constant distraction, our attention is frequently directed away from activities that create genuine happiness. We optimise for variables, like wealth, status, or social media metrics, that capture our attention but may contribute little to experienced or evaluative well-being.

Applied Happiness: Finding Balance Between Our Two Selves

Recognising the distinction between our experiencing and remembering selves offers practical guidance for better decisions. Rather than blindly following either self, we can seek balance, creating positive memories while also attending to moment-by-moment experiences.

For relationships, this might mean acknowledging that daily interactions matter alongside special occasions. A marriage with warm everyday connections but modest anniversaries might provide more total happiness than one with spectacular celebrations interspersed with daily friction.

For work, it suggests balancing achievements (which satisfy the remembering self) with engagement (which pleases the experiencing self). Career decisions that consider meaningful accomplishment and day-to-day enjoyment are more likely to provide lasting satisfaction.

For leisure, it means recognising when we’re sacrificing too much present enjoyment for future memories. Taking photographs throughout a special event might create better memories at the cost of fully experiencing the moment, a trade-off worth considering consciously rather than defaulting to either extreme.

Most importantly, awareness of these two selves helps us avoid common decision-making traps. Understanding that our memories differ systematically from our experiences allows us to compensate for these differences when making choices that affect our future selves.

Kahneman’s Scientific Humility and Lasting Impact

What struck me most about Kahneman wasn’t just the brilliance of his insights but also the humility with which he pursued them. Throughout his career, he demonstrated a rare quality among prominent academics: a willingness to question his own thinking and openly acknowledge his errors. This characteristic made his work not just intellectually significant but personally inspiring.

The Rare Genius Who Questioned His Own Thinking

Unlike many influential thinkers who defend their theories against all challenges, Kahneman consistently subjected his own ideas to the same scrutiny he applied to conventional wisdom. In “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” he candidly discusses his mistakes and the limitations of his research.

When describing a study he conducted with Amos Tversky on statistical intuitions among professional researchers, Kahneman admits:

Our (Kahneman and Tversky’s) subjective judgements were biased: we were far too willing to believe research findings based on inadequate evidence… The goal of our study was to examine whether other researchers suffered from the same affliction.

This self-awareness extended to his personal biases. He acknowledges falling prey to the very cognitive errors he documented in others: overconfidence, hindsight bias, and the planning fallacy. When recounting a project that ran years longer than expected, he calls it “one of the most instructive experiences of my professional life,” detailing three lessons from this failure.

This combination of intellectual achievement and personal modesty created a powerful model for scientific inquiry. By treating himself as a subject of his own research, Kahneman demonstrated that recognising our cognitive limitations isn’t a weakness but a prerequisite for clearer thinking.

His approach resonates strongly with my own belief in continuous learning and self-examination. While I lack Kahneman’s brilliance, I’ve always valued the willingness to question one’s assumptions and learn from mistakes. This quality seems increasingly rare in public discourse.

Beyond Economics: How Kahneman Changed Multiple Fields

Few academics have influenced as many disciplines as Kahneman. His work with Tversky began as basic research in cognitive psychology. Still, it expanded to transform economics, medicine, law, public policy, and business.

Prospect Theory challenged the dominant model of human behaviour in economics, eventually giving rise to behavioural economics, now a major field in its own right. Richard Thaler, who received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2017, built directly on Kahneman’s insights, developing practical applications like “nudges” that help people make better choices without restricting freedom.

Kahneman’s work on judgement under uncertainty has improved diagnostic procedures and treatment decisions in medicine. Awareness of cognitive biases has led to checklists and decision-support tools that reduce errors and increase consistency in patient care.

In law, his research on hindsight bias (our tendency to believe we could have predicted events once we know the outcome) has influenced how courts evaluate negligence claims. His work on framing effects has enhanced understanding of how juries respond to different presentations of identical evidence.

In business, Kahneman’s insights have transformed practices from hiring to strategic planning. Companies now implement structured interviews to counter biases, employ premortems to identify potential project failures before they occur, and design choice architectures that help consumers make better decisions.

These practical applications reflect Kahneman’s commitment to research that matters beyond the laboratory. While he conducted precise, controlled experiments, he never lost sight of their real-world implications. His work helps explain everyday phenomena, from market bubbles to medical errors, political polarisation, and personal financial mistakes.

The Future of Behavioural Science After Kahneman

Kahneman’s death marks the end of an era in behavioural science. Still, his influence continues to grow through the work of researchers and practitioners he inspired. Several key developments suggest how his legacy will evolve in the coming decades.

First, behavioural science is increasingly integrated with neuroscience, revealing the neural mechanisms behind the cognitive processes Kahneman identified. Functional MRI studies now show how different brain regions activate during intuitive versus deliberative thinking, providing physical evidence for the two-system model.

Second, the digital age offers unprecedented opportunities to study human behaviour at scale. Online platforms can test behavioural interventions with millions of participants, providing insights that weren’t possible with traditional laboratory methods. These large-scale studies help refine our understanding of when and how cognitive biases operate in diverse populations.

Third, behavioural insights are becoming essential in addressing major societal challenges. Climate change, public health, financial stability, and digital privacy all involve human decision-making under uncertainty—precisely the domain where Kahneman’s work provides crucial guidance.

Perhaps most importantly, Kahneman’s ideas have entered the cultural mainstream, changing how people understand their own minds. Concepts like System 1 and System 2, loss aversion, and the planning fallacy now appear in everyday conversation, helping people recognise and sometimes counteract their own biases.

Personal Reflections: What Kahneman Taught Me

Re-reading my notes on “Thinking, Fast and Slow” after learning of Kahneman’s passing, I’m struck by how deeply his ideas have shaped my approach to research and daily decisions. Three lessons stand out particularly:

First, he taught me to distinguish between confidence and certainty, to recognise that feeling sure doesn’t mean I’m right. This awareness has made me more open to revising my views when new evidence emerges, something I find essential in both professional and personal contexts.

Second, his work revealed how our environment powerfully shapes our choices, often without our awareness. This understanding has helped me design better systems for myself rather than relying solely on willpower, such as removing social media apps from my phone.

Third, his distinction between experiencing and remembering selves has changed how I think about time allocation. I pay more attention to everyday experiences rather than focusing exclusively on achievements that will make for good stories later.

These lessons don’t mean I avoid the biases and errors Kahneman documented—I certainly don’t. But awareness of these patterns provides a chance to catch myself mid-error, to pause when making important decisions, and to consider whether my intuitive response might be leading me astray.

As I reflect on Kahneman’s legacy, what stands out most is the rare combination of qualities he embodied: intellectual boldness paired with personal humility, rigorous science directed at practical problems, and a genuine curiosity about the workings of the human mind.

His passing is a significant loss, but the intellectual tools he provided will continue to help us circumnavigate our complex world with greater wisdom and self-awareness.

Sources

- Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books, 2011.

Credits

Featured image: ‘World Economic Forum’