Advice to all parents: if you’re poor, become rich. If your child happens to be female then trade her in for a male. If you’re thinking of sending your child to a good university, forget this and only aim for a top university. If you happen to come from a poor social background then you really need to step up and get out of it. A study has found that potential graduate earnings can be impacted by these factors.

The last two blog posts by ND presented two ways in which parents can help their kids identify their creative calling, by understanding Multiple Intelligences and Signature Strengths. Now, a creditable report has found graduate earnings to be linked to gender, wealth, institution, course and socio-economics, which would suggest that efforts should be spent instead on ensuring your child goes to a top university and that they select medicine or economics as a degree subject. Though a parent cannot change their level of wealth or social background overnight, or the gender of their children, they can help them to pick the right university and subject.

Report highlights

- Graduates from affluent families earn considerably more after leaving university than students from poorer backgrounds.

- In almost every degree subject, men earn more a decade into their careers than women.

- Ten years after graduation, male medical students earn a median (average) wage of £55,000 a year, while female medical students typically earn a median wage of £45,000 a year.

- Students of the London School of Economics, Oxford and Cambridge earn the most.

- Higher earners tend to come from wealthier backgrounds.

- Higher education leads to much better earnings than non-graduate salaries.

Those behind the report

The report was funded by the Nuffield Foundation and compiled by researchers at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), University College London (UCL) Institute of Education, Harvard University and the University of Cambridge.

IFS, based in London, is an economic research institute, with specialist knowledge on UK taxation and public policy. They are an independent body producing academic and policy-related studies.

How the authors arrived at their conclusions

The research used anonymised tax data and student loan records for 260,000 students up to ten years after graduation. Government departments hold this information in order to carry out large-scale studies, looking at outcomes over many years. This is the first time a ‘big data’ approach has been used to examine how graduate earnings vary by institution of study, degree subject and parental income.

The data set includes cohorts of graduates who started university in the period 1998–2011 and whose earnings (or lack of) were observed over a number of tax years. The paper largely focuses on the tax year 2012/13.

The argument about the gender gap just want go away!

The gender pay gap was particularly noticeable amongst higher earners, even if both female and male students studied the same course at the same university. Females are regularly appearing as being paid less than their male counterparts.

The report shows that male students earned more than female students in every subject, with the exception of European languages and literature, in which females earned more. On average, female graduates earn around £3,000 less each year ten years after completing their studies: male graduates earned an annual wage of £17,900, and female graduates earned £14,500. See Table 1.

Table 1: Earnings by subject ten years after graduation for females and males

| Degree | Female Salary | Male Salary |

| Medicine | £45,400 | £55,300 |

| Economics | £38,200 | £42,000 |

| Engineering and technology | £23,200 | £31,200 |

| Law | £26,200 | £30,100 |

| Physical Sciences | £24,800 | £29,800 |

| Education | £24,400 | £29,600 |

| Architecture | £22,500 | £28,600 |

| Maths and Computer science | £22,000 | £26,800 |

| Business | £22,000 | £26,500 |

| History and philosophy | £23,200 | £26,500 |

| Social sciences | £20,500 | £26,200 |

| Biological sciences | £23,800 | £25,200 |

| European languages and literature | £26,400 | £25,000 |

| Linguistics and classics | £23,200 | £24,100 |

| Veterinary and agriculture | £18,900 | £21,400 |

| Mass communication | £18,100 | £19,300 |

| Creative arts | £14,500 | £17,900 |

Source: IFS (based on median annual salary)

What the report said about those with degrees and those without degrees

The study also showed that graduates are much more likely to have a job and to earn more than non-graduates, who are twice as likely to have no earnings compared to graduates ten years on.

Due to low employment status, half of non-graduate women had earnings below £8,000 a year at around age 30. Only a quarter of female graduates were earning less than this. Half were earning more than £21,000 a year.

For those with significant earnings (the report defines this as above £8,000 a year), average earnings for male graduates ten years after graduation were £30,000, and, for non-graduates of the same age, average earnings were £22,000. The equivalent figures for females with significant earnings were £27,000 and £18,000 respectively.

Parental income influences how much a child can earn

Graduates from wealthy households earn significantly more after leaving university than students from poorer backgrounds, who do the same degree at the same university.

Taking into account the subject studied and university attended the average student from a higher-income background (defined as being from approximately the top 20% of households of those applying to higher education) earned around 10% more in the labour market than the average student from poorer backgrounds (the other 80% of students).

To put this into perspective, the 10% highest-earning male graduates from richer backgrounds earned about 20% more than the 10% highest earners from relatively poorer backgrounds.

The equivalent premium for the 10% highest-earning female graduates from richer backgrounds was 14%.

The university your child goes to has an influence on their potential earnings

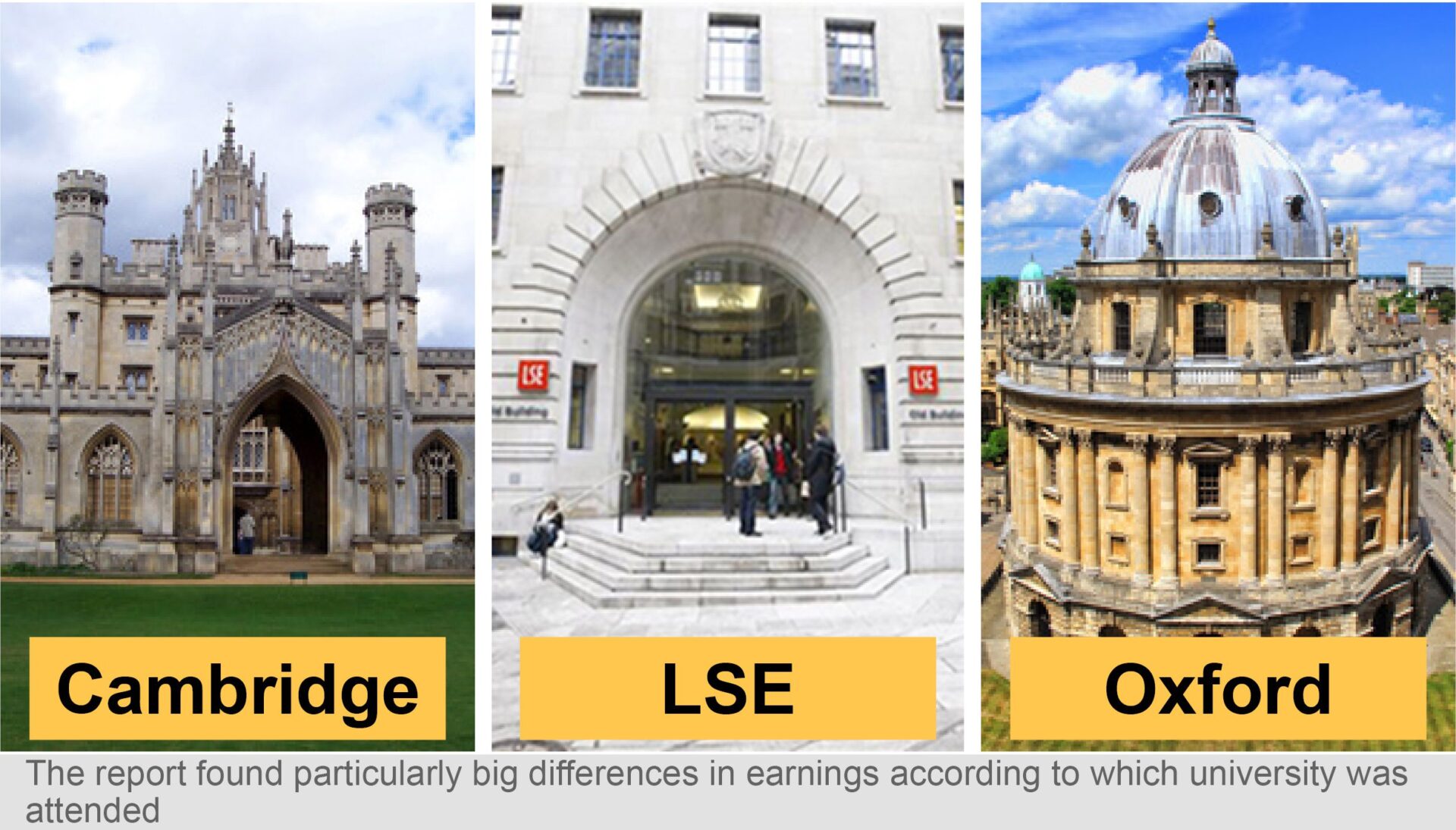

The London School of Economics (LSE) was the most lucrative university, according to the study, followed by Cambridge and then Oxford, which also happen to be the best universities in the UK. The researchers did mention that LSE benefited from offering high-paying subjects like economics and law.

Around 10% of male graduates from LSE, Oxford and Cambridge were earning in excess of £100,000 a year ten years after graduation in 2012/13, with LSE graduates earning the most. LSE was the only institution with more than 10% of its female graduates earning in excess of £100,000 at year ten years on.

At the other end of the scale, there were some institutions (23 for men and 9 for women) where the average graduate earnings were less than those of the average non-graduate ten years on.

The subject your child chooses does have an impact on their earnings

Those who studied medicine and economics were found to earn significantly more than those reading other subjects. Those with qualifications in the fields of engineering and technologies, education, and law have gone on to make up the rest of the top five highest-paid graduates.

Medical graduates earned a median wage of around £50,000 for men and around £45,000 for women after ten years. Economics was the second most lucrative degree, with male students earning a median salary of £42,000, and women earning £38,000.

For males, it was estimated that approximately 12% of economics graduates earned above £100,000 some ten years after graduation; by contrast, 6% of those studying medicine or law earned more than £100,000.

For females, it was estimated that approximately 9% of economics graduates earned above £100,000 some ten years after graduation; by contrast, just 1% of those studying medicine and 3% of those studying law did so.

Those who obtained degrees in creative arts had the lowest salaries, with an average wage of £17,900 for men and £14,500 for women.

So what did the researchers who conducted the study have to say about their findings?

Jack Britton from IFS and the main author of the study said:

This work shows that the advantages of coming from a high-income family persist for graduates right into the labour market at age 30. While this finding doesn’t necessarily implicate either universities or firms, it is of crucial importance for policymakers trying to tackle social immobility.

Anna Vignoles of the University of Cambridge said students should think carefully about what they choose to study:

The research illustrates strongly that for most graduates, higher education leads to much better earnings than those earned by non-graduates, although students need to realise that their subject choice is important in determining how much of an earnings advantage they will have.

Neil Shephard of Harvard University said:

Earnings vary substantially with university, subject, gender and cohort. This impacts on which parts of the HE sector the UK government funds through the subsidy inherent within income-contingent student loans. The next step in the research is to quantify that variation in funding, building on today’s paper.

ND’s views

For any parent, advising their children on the best subjects to do at A Level and for their degree becomes difficult. Whilst every child should be given the freedom to do what they want, care must be taken in deciding what they actually study and the prospects that await them once their degree is completed.

The world’s economic state puts pressure on this decision: obtaining a mortgage to buy a house is no longer easy, with 35 being the average age for first-time buyers, and it is predicted that will rise to 41 by the year 2025. No wonder some parents will most likely sound the cautious note to any child wanting to select a subject which does not appear in the top five of Table 1.

Are we in danger of ignoring what our children are strongest at, and what they could therefore contribute to society in the future, if we force them into choosing a subject where money and earnings are the predominant incentives? Whilst the cost of living may be increasing in many parts of the world, temptation to select a subject based on earnings will influence some, but surely the only option should be a child’s natural calling.

Does a conformist child have a better chance in life than one who finds and pursues their creative calling? There are many that will conform by basing their subject selection on future earnings. Trying to counteract this will be those that follow their natural calling, where passion and creativity lead this choice.

In many cases both sets of kids will get by in life, albeit with one earning significantly more than the other. But are we suddenly all going to force our kids to think very carefully about what they do and where they study – if they meet the requirements? After all, there is not much that can be done regarding gender or level of family wealth in the 80% of us who are not at the top end of that scale. But in the future, depending on your child’s choices, their children might very well have wealth on their side too.

The power of earnings cannot be ignored, although I believe the majority of parents will be supportive of their kid’s choices, even if they know this will mean they will not reach the higher-earner ranks. The report does not provide an insight into job satisfaction and happiness of the graduates and I suspect that this would tell a different story.

Sources

- Jack Britton, J., Dearden, L., Shephard, N. and Vignoles, A. (2016) How English domiciled graduate earnings vary with gender, institution attended, subject and socio-economic background (Executive Summary), Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Accessed 13th April 2016]

- Jack Britton, J., Dearden, L., Shephard, N. and Vignoles, A. (2016) How English domiciled graduate earnings vary with gender, institution attended, subject and socioeconomic background, Institute for Fiscal Studies, Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Accessed 13th April 2016]

Source: IFS (based on median annual salary)

What the report said about those with degrees and those without degrees

The study also showed that graduates are much more likely to have a job and to earn more than non-graduates, who are twice as likely to have no earnings compared to graduates ten years on.

Due to low employment status, half of non-graduate women had earnings below £8,000 a year at around age 30. Only a quarter of female graduates were earning less than this. Half were earning more than £21,000 a year.

For those with significant earnings (the report defines this as above £8,000 a year), average earnings for male graduates ten years after graduation were £30,000, and, for non-graduates of the same age, average earnings were £22,000. The equivalent figures for females with significant earnings were £27,000 and £18,000 respectively.

Parental income influences how much a child can earn

Graduates from wealthy households earn significantly more after leaving university than students from poorer backgrounds, who do the same degree at the same university.

Taking into account the subject studied and university attended the average student from a higher-income background (defined as being from approximately the top 20% of households of those applying to higher education) earned around 10% more in the labour market than the average student from poorer backgrounds (the other 80% of students).

To put this into perspective, the 10% highest-earning male graduates from richer backgrounds earned about 20% more than the 10% highest earners from relatively poorer backgrounds.

The equivalent premium for the 10% highest-earning female graduates from richer backgrounds was 14%.

The university your child goes to has an influence on their potential earnings

The London School of Economics (LSE) was the most lucrative university, according to the study, followed by Cambridge and then Oxford, which also happen to be the best universities in the UK. The researchers did mention that LSE benefited from offering high-paying subjects like economics and law.

Around 10% of male graduates from LSE, Oxford and Cambridge were earning in excess of £100,000 a year ten years after graduation in 2012/13, with LSE graduates earning the most. LSE was the only institution with more than 10% of its female graduates earning in excess of £100,000 at year ten years on.

At the other end of the scale, there were some institutions (23 for men and 9 for women) where the average graduate earnings were less than those of the average non-graduate ten years on.

The subject your child chooses does have an impact on their earnings

Those who studied medicine and economics were found to earn significantly more than those reading other subjects. Those with qualifications in the fields of engineering and technologies, education, and law have gone on to make up the rest of the top five highest-paid graduates.

Medical graduates earned a median wage of around £50,000 for men and around £45,000 for women after ten years. Economics was the second most lucrative degree, with male students earning a median salary of £42,000, and women earning £38,000.

For males, it was estimated that approximately 12% of economics graduates earned above £100,000 some ten years after graduation; by contrast, 6% of those studying medicine or law earned more than £100,000.

For females, it was estimated that approximately 9% of economics graduates earned above £100,000 some ten years after graduation; by contrast, just 1% of those studying medicine and 3% of those studying law did so.

Those who obtained degrees in creative arts had the lowest salaries, with an average wage of £17,900 for men and £14,500 for women.

So what did the researchers who conducted the study have to say about their findings?

Jack Britton from IFS and the main author of the study said:

This work shows that the advantages of coming from a high-income family persist for graduates right into the labour market at age 30. While this finding doesn’t necessarily implicate either universities or firms, it is of crucial importance for policymakers trying to tackle social immobility.

Anna Vignoles of the University of Cambridge said students should think carefully about what they choose to study:

The research illustrates strongly that for most graduates, higher education leads to much better earnings than those earned by non-graduates, although students need to realise that their subject choice is important in determining how much of an earnings advantage they will have.

Neil Shephard of Harvard University said:

Earnings vary substantially with university, subject, gender and cohort. This impacts on which parts of the HE sector the UK government funds through the subsidy inherent within income-contingent student loans. The next step in the research is to quantify that variation in funding, building on today’s paper.

ND’s views

For any parent, advising their children on the best subjects to do at A Level and for their degree becomes difficult. Whilst every child should be given the freedom to do what they want, care must be taken in deciding what they actually study and the prospects that await them once their degree is completed.

The world’s economic state puts pressure on this decision: obtaining a mortgage to buy a house is no longer easy, with 35 being the average age for first-time buyers, and it is predicted that will rise to 41 by the year 2025. No wonder some parents will most likely sound the cautious note to any child wanting to select a subject which does not appear in the top five of Table 1.

Are we in danger of ignoring what our children are strongest at, and what they could therefore contribute to society in the future, if we force them into choosing a subject where money and earnings are the predominant incentives? Whilst the cost of living may be increasing in many parts of the world, temptation to select a subject based on earnings will influence some, but surely the only option should be a child’s natural calling.

Does a conformist child have a better chance in life than one who finds and pursues their creative calling? There are many that will conform by basing their subject selection on future earnings. Trying to counteract this will be those that follow their natural calling, where passion and creativity lead this choice.

In many cases both sets of kids will get by in life, albeit with one earning significantly more than the other. But are we suddenly all going to force our kids to think very carefully about what they do and where they study – if they meet the requirements? After all, there is not much that can be done regarding gender or level of family wealth in the 80% of us who are not at the top end of that scale. But in the future, depending on your child’s choices, their children might very well have wealth on their side too.

The power of earnings cannot be ignored, although I believe the majority of parents will be supportive of their kid’s choices, even if they know this will mean they will not reach the higher-earner ranks. The report does not provide an insight into job satisfaction and happiness of the graduates and I suspect that this would tell a different story.

Sources

- Jack Britton, J., Dearden, L., Shephard, N. and Vignoles, A. (2016) How English domiciled graduate earnings vary with gender, institution attended, subject and socio-economic background (Executive Summary), Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Accessed 13th April 2016]

- Jack Britton, J., Dearden, L., Shephard, N. and Vignoles, A. (2016) How English domiciled graduate earnings vary with gender, institution attended, subject and socioeconomic background, Institute for Fiscal Studies, Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Accessed 13th April 2016]