The relationship between sleep and education first captured my attention through Matthew Walker’s thought-provoking book “Why We Sleep”. As I turned each page, his insights resonated deeply with my experiences as a father, sparking a personal connection with the topic.

Living between the UK and the Middle East opened my eyes to how different school start times affect children’s learning. These personal observations and Walker’s compelling evidence sparked my interest in understanding sleep’s role in our lives.

My earlier posts examining sleep facts and digging into sleep science revealed startling patterns. This led me to explore how sleep and education shape our children’s development.

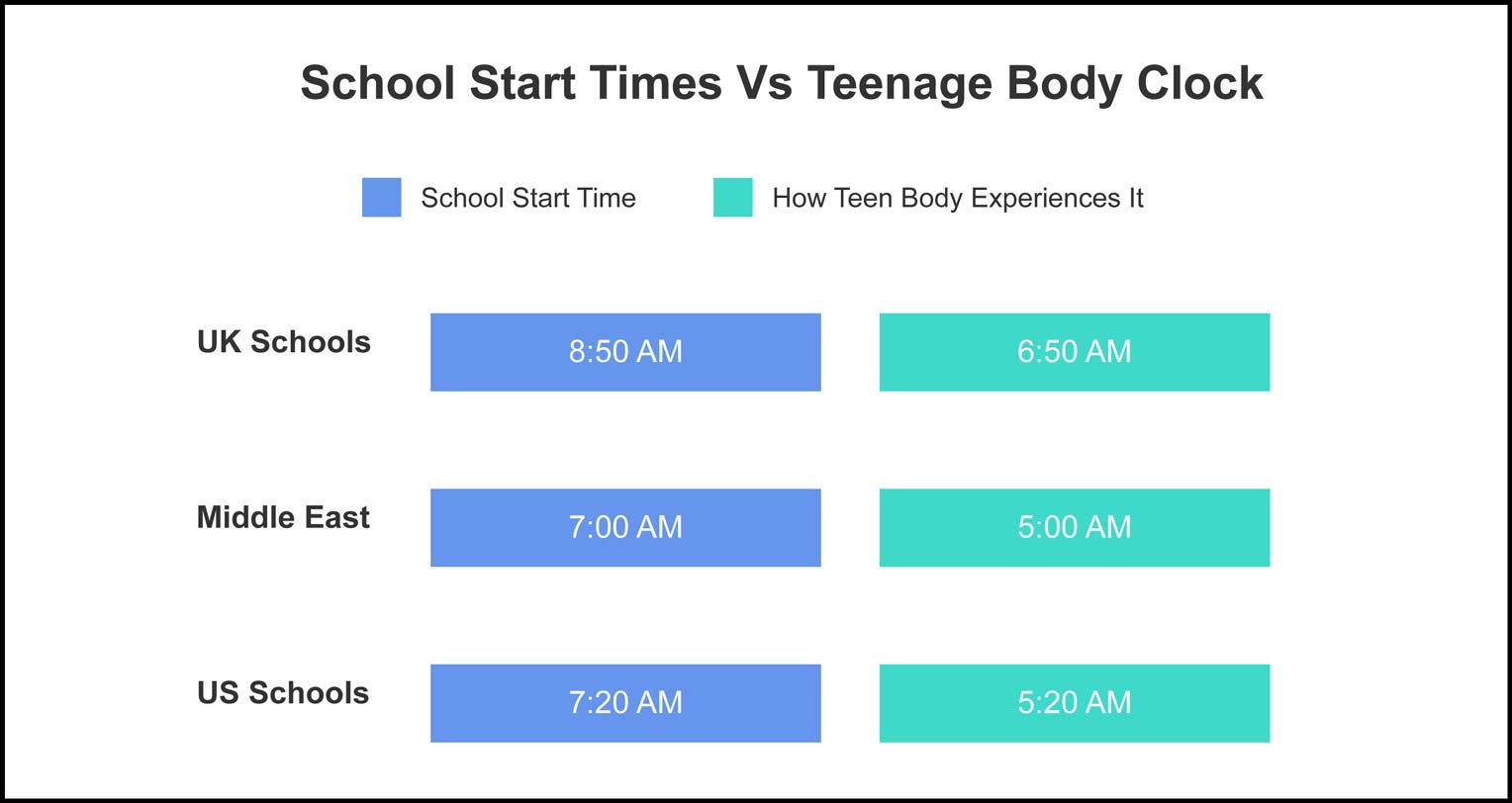

A study of 750,000 schoolchildren aged 5-18 uncovered a concerning trend – today’s students sleep two hours less than their counterparts from a century ago. For teenagers, this shortfall creates significant challenges. When a teenager wakes at 5:15 AM, their body responds as if it were 3:15 AM for an adult. Picture yourself solving complex equations at that hour.

Insufficient sleep affects every learning aspect. Students struggle with memory formation, attention spans waver, and emotional regulation becomes challenging. Through my children’s experiences in different school systems, I’ve watched these effects play out daily.

The pages ahead reveal surprising insights about sleep’s influence on academic performance. We’ll examine biological sleep patterns, question traditional school timings, and uncover unexpected connections to ADHD diagnoses. These findings might change how you view your child’s education, mainly if they have been diagnosed with or are showing symptoms of ADHD.

Sleep and Education: A Critical Relationship

The link between sleep and education becomes apparent through my three children’s experiences with different school timings. Starting times varied by 3 hours in the winter and 2 hours in the summer between the UK and the Middle East, giving me a unique perspective on how timing affects learning ability. I vividly remember the difference in their energy levels and enthusiasm for learning based on the school start times.

My children’s performance shifted noticeably with these different schedules. In the UK, with 8:50 AM starts, they arrived alert and ready to learn. The Middle East’s 7:00 AM starts often left them struggling to focus through morning lessons. Matthew Walker emphasises this timing impact:

To persist in this way is to run the cup over children with partial amnesia. Forcing youthful brains to become early birds will guarantee that they do not catch the worm, if the worm in question is knowledge or good grades.

The evidence supporting later start times grows stronger each year. Studies tracking 750,000 students reveal modern children sleep two hours less than previous generations. This reduction in sleep creates a cascade of effects on learning, memory, and attention.

The implications of sleep and education patterns affect academic performance, emotional regulation, social interactions, and overall well-being. When examining my children’s behaviour after different qualities of sleep, these effects become unmistakable.

Understanding Teen Sleep Biology

The teenage years bring distinct biological changes to sleep patterns. Children’s transition into adolescence reveals how sleep and education systems often clash with natural rhythms.

Teenagers experience a significant forward shift in their sleep timing. Their bodies naturally want to sleep and wake later – a pattern entirely at odds with typical school schedules. This isn’t laziness; it’s biology at work. Walker describes this mismatch perfectly:

When we ask teens to wake up at 6 AM for school, it’s equivalent to waking adults up at 3 AM. We wouldn’t ask adults to give a presentation at this hour, yet we ask teens to learn calculus.

This biological shift affects 90% of teenagers worldwide, regardless of culture or geography. Their circadian rhythms naturally push sleep onset to about 11 PM, making early school starts particularly challenging. The current sleep and education model ignores these biological imperatives.

Sleep must remain high during adolescence at 9-10 hours per night. Yet most teenagers average only 6.5-7.5 hours. This gap between need and reality affects their ability to learn, remember, and regulate emotions.

Watching teenagers struggle against their natural sleep patterns while trying to maintain good grades highlights the urgency of addressing this issue. The current system places unnecessary barriers between students and their biological needs, which demands immediate attention and action.

Early School Times Create Learning Barriers

Starting classes before 7:20 AM forces half of US students to wake in darkness. Starting at 8:50 AM, UK pupils gain precious morning sleep that enhances their learning capacity. These contrasting times in sleep and education schedules highlight a growing concern for students worldwide.

Dr Lewis Terman, creator of the IQ test (revision of the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales), uncovered a simple truth – the longer children sleep, the better they perform intellectually. His findings showed reasonable school start times aligned perfectly with students’ natural biological rhythms. Matthew Walker articulates this powerfully:

We are creating a generation of disadvantaged children, hamstrung by sleep deprivation. Later start times are clearly, then literally, the smart choice.

Children stumble through lessons in a half-conscious state, chronically sleep-deprived year after year. This affects their mental growth and limits their success potential. The current sleep and education system imposes unnecessary barriers between students and achievement.

Studies examining 260,000 students reveal how early starts fragment sleep patterns. We tear teenagers from their beds each morning during their deepest sleep phase, precisely when their brains process the previous day’s learning.

Sleep and Education Link to ADHD Diagnosis

Findings highlight how sleep loss mimics ADHD symptoms in children. Students who lack proper rest become irritable and unfocused and display behavioural difficulties that mirror attention deficit patterns.

Take a child to their doctor describing these symptoms without mentioning sleep habits, and what follows? There is not a discussion about rest, but it is often an ADHD diagnosis. The overlap between sleep deprivation and sleep and education challenges creates a concerning pattern. Walker notes this alarming trend:

Sleep-deprived children become moodier, more impulsive, and struggle with sustained attention. We’re potentially misdiagnosing exhausted students with ADHD.

Students experiencing insufficient sleep show striking changes. They become anxious, struggle with emotional control, and lose focus during lessons. The symptoms intensify as sleep and education pressures mount through the academic year.

This creates a troubling cycle. Sleep-deprived children struggle academically, leading to increased stress, which further disrupts their sleep. Without addressing the root cause, we risk overlooking simple solutions in favour of more complex diagnoses.

Breaking the Generational Sleep Crisis

During my years as an athlete, coaches stressed the importance of proper rest for physical performance. Yet somehow, while we protect athletes’ sleep, we overlook its value in sleep and education settings where mental performance matters most.

Traditional school timings persist despite mounting evidence against them. Nearly 80% of adults recall receiving guidance about exercise, drugs, and reproductive health during their education. Yet discussions about sleep – a cornerstone of learning and development – remain absent from most curricula. Matthew Walker shares this observation:

Sleep holds no volume in the current education system. Without change, we continue the generational cycle of sleep deprivation’s dangers.

The consequences reach far into students’ futures. Poor sleep patterns established during school years often lead to lifelong sleep difficulties. These habits affect career choices, relationships, and mental health outcomes throughout adulthood. The sleep and education relationship shapes life trajectories in ways we’re only beginning to appreciate.

As a researcher and father, I’ve witnessed how proper rest transforms learning ability. Whether in laboratories or living rooms, the evidence points clearly toward change. Our children deserve educational systems that work with their biology, not against it.

Sources

- Campbell IG, Van Dongen HPA, Gainer M, Karmouta E, Feinberg I. Differential and interacting effects of age and sleep restriction on daytime sleepiness and vigilance in adolescence: a longitudinal study. Sleep. 2018;41:zsy177.

- Cortese S, Brown TE, Corkum P, et al. Assessment and management of sleep problems in youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52:784–96.

- Cremone A, Lugo-Candelas CI, Harvey EA, McDermott JM, Spencer RMC. REM theta activity enhances inhibitory control in typically developing children but not children with ADHD symptoms. Exp Brain Res 2017;235:1491–500.

- Kaplan K.A., Hardas P.P., Redline S., Zeitzer J.M., Sleep Heart Health Study Research Group. Correlates of sleep quality in midlife and beyond: A machine learning analysis. Sleep Med. 2017;34:162–167.

- Matthew Walker “Why We Sleep” Waterstones

- McLaughlin Crabtree V., Beal Korhonen J., Montgomery-Downs H.E., Faye Jones V., O’Brien L.M., Gozal D. Cultural influences on the bedtime behaviors of young children. Sleep Med. 2005;6(4):319–324.

- O’Donnell D., Silva E.J., Münch M., Ronda J.M., Wang W., Duffy J.F. Comparison of subjective and objective assessments of sleep in healthy older subjects without sleep complaints. J. Sleep Res. 2009;18:254–263.

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1255–1273.

- Peirano P, Algarín C, Garrido M et al. Iron-deficiency anemia is associated with altered characteristics of sleep spindles in NREM sleep in infancy. Neurochem Res 32, 1665–1672.

- Tarokh L., Saletin J.M., Carskadon M.A. Sleep in Adolescence: Physiology, Cognition and Mental Health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016;70:182–188.

- Wheaton A.G. Sleep Duration and Injury-Related Risk Behaviors Among High School Students—United States, 2007–2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016;65:337–341.

- Wright KP, Frey DJ. Age related changes in sleep and circadian physiology: from brain mechanisms to sleep behavior. In: Avidan AY, Alessi C, Geriatric Sleep Medicine. New York (NY): CRC Press; 2009, p. 1-18.